Chapter 4: [Key #4] Why We Really Fall In Love: The Cold Heart Truth

“The only way to appreciate something’s value is to distance yourself from it for a while”

– Goombah Guru

Georg Simmel

In order to find out why a person becomes attracted to another individual, we must first ask ourselves what makes anything valuable and thus, desirable. We will begin this task by discussing Georg Simmel’s generic definition of the concept “value.” In his book The Philosophy of Money, Simmel offers a useful examination of the concept. That is, he sketches out a logical sequence on how social objects become valuable. For the purpose of our discussion about relationships, people are viewed as social objects in this model.

Simmel’s Book: The Philosophy of Money

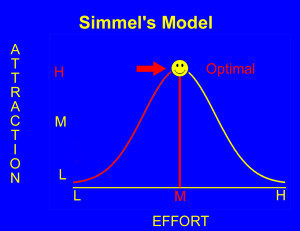

In Simmel’s view, what makes something valuable is the “distance” between the object itself and the person desiring it. According to Simmel, overcoming the distance between the person desiring something and the item itself is what makes an object desirable (value). Because closing such distance requires one to exert some sort of “effort,” the object’s desirability (or value) is measured by how much work must be put into closing that distance. In other words, the more effort it takes to earn an object, the more value that object takes on. The less effort it takes to obtain an object; the less valuable that object becomes. Simmel’s logic seems simple enough.

“… the most valuable objects are the ones that are neither too close, too easily obtainable, nor are too far; and/or difficult to obtain… “

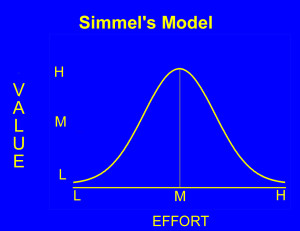

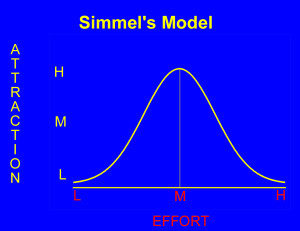

Simmel’s Model of Value.

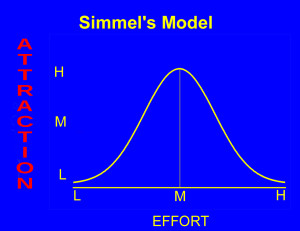

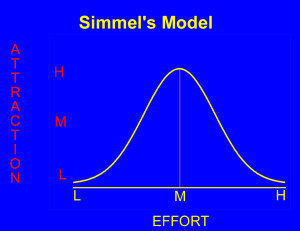

For purposes of our discussion, we’re going to substitute Simmel’s value label in the chart and re-label it as attraction (see diagram below). After all, the value we are talking about relates to a person. In other words, we are going to treat the concept of value as being the same thing as attraction.

Simmel’s Model with ATTRACTION Substituted for VALUE.

The crux of the book is based on Simmel’s logic about what makes anything valuable; or in our case attractive. This point is so important that it bears repeating. Simmel argued that expending effort to close some sort of “distance” that separates a person and the object of their desire is what makes anything valuable to them. The person that has to earn an individual’s love and affection will become attracted to that individual. On the other hand, if a person doesn’t have to expend very much effort to gain an individual’s love and affection, that person won’t be very attracted to that individual.

For example, let’s say that you desire a Porsche. Under normal circumstances, you would have to work long hours and expend a significant amount of effort to acquire such a luxurious automobile. Thus, after expending so much energy to purchase that Porsche, you would surely value it. You would certainly appreciate that Porsche and would probably even take good care of it.

The “Value Formula”.

Simmel centers his argument on the concept of effort. It takes effort to “earn” someone’s love and affection. According to The Value Formula, if a person has to expend a significant amount of effort to earn an object, they will come to appreciate it. And it’s objects we come to appreciate that we deem valuable (or as having some worth).

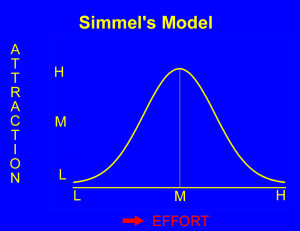

The Concept of EFFORT.

There are three possible levels of effort required to earn someone’s love. There can be a low level of effort required to earn someone’s love. There also exists the possibility of a medium level of effort being required to earn someone’s love. And last, there exists the possibility of a high level of effort required to earn someone’s love.

This means that on one end of the continuum, some people are “easy to get.” In the middle of that continuum, there are people that are “hard to get.” While on the other end of the continuum, there are people who are “impossible to get.”

These levels of effort, however, aren’t set in stone. In fact, they should be conceptualized as being fluid in nature. A person who is “easy to get” one day may become “hard to get” the next day and vice versa. It all depends on what’s happening in such a person’s life.

For example, someone could be “easy to get” one day, and then say they quickly become somewhat famous overnight. This person may let the instant fame go to their head and suddenly become big-headed and picky about whom they consider a worthy romantic partner.

Just like the concept of effort, there are also three corresponding levels of attraction. There can be a low level of attraction to another person; as well as a medium or a high level of attraction to a person (see diagrams below).

So far I have introduced and discussed the two basic conceptual ingredients needed to help us understand how attraction emerges and develops; they are effort and attraction. We have seen that there are three possible levels of effort needed to earn a person’s love and affection. We have also seen that there are three possible levels of attraction someone can feel toward a person.

EFFORT = LOW – MEDIUM – HIGH.

ATTRACTION = LOW … MEDIUM … HIGH.

Our task now is to see how these concepts are related to one another. Once we determine the relationship between these concepts, we will begin to understand how they affect how deeply a person will fall in love. This is where our discussion gets interesting. I want to take this opportunity to point out that the next section of this chapter is the most important of this book

Simmel based his argument about what created value on the concept of the amount of effort a person had to expend to get another individual’s attention (or love). His claim was that value depended on how much effort was required to close the “distance” that stood between something (in our case someone) and the person desiring said object (their love interest). But let me remind you that for our purpose of better understanding why people become attracted to a person, we will be substituting Simmel’s concept of value for the idea of attraction (or love).

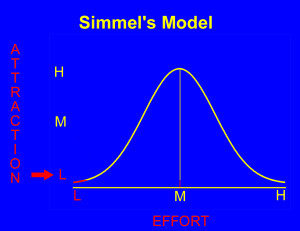

By this point in the discussion you know that a low level of effort will result in a low level of attraction. In other words, if a person is too “easy to get,” their love and affection will be taken for granted. And who do you know that is attracted to someone that everyone can have for practically nothing?

Low EFFORT = Low ATTRACTION.

Based on the logic we have been discussing, you’ve probably figured out that a medium level of effort will thus result in an average amount of attraction (love). According to the same logic discussed in the two previous sentences, then a high level of effort should result in a high level of attraction (love). But such is not the case.

“The most valuable persons are the ones who are “hard to get,” but who are not “impossible to get.”

Simmel cautioned against conceptualizing value in too simplistic of terms; like the ones we just discussed in the preceding paragraph. He maintained that if the distance is too narrow- too easy to overcome, it renders the object valueless. Yet, on the other hand, if the distance is too wide, and virtually insurmountable, the object also ceases to be of much value.

Using simple logic, someone may think that high effort should correspond exactly with high attraction. But as Simmel cautioned, if it requires too much effort to earn someone’s love and affection, it may mean that “the juice is no longer worth the squeeze.”

Thus, according to Simmel, the optimal distance a person needs to overcome in order to be attracted to another individual is one that is neither too close nor too far. When using Simmel’s logic to examine relationships, the most valuable persons are the ones who are “hard to get,” but who are not “impossible to get.”

The Optimal Level of Attraction.

What defines the optimal effort to attraction balance is someone who is not too near (easy “to get”) or too far (impossible “to get). Simmel calls these parameters the “upper” and “lower” real-limits. If you’re too easy to get, you will get kicked to the curb. If you’re too distant, someone may feel that it’s not worth the effort to pursue you. Again, I reference the “juice” and the “squeeze.”

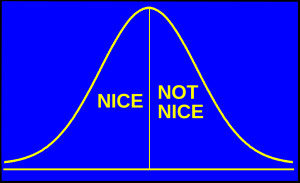

The logic behind this way of thinking should be thought of as being fluid in nature. When someone is with an individual who they wish treated them better, they fantasize about being with a nice guy; so they think. In contrast to the unpleasant guy, the nice guy doesn’t seem like so much work. So they convince themselves that they want a nice guy. Yet, when they begin dating that nice guy they envisioned as the answer to their relationship problems, how long is it until they become bored and end up wanting more of a dating challenge? Sometimes if you get caught up in this crazy phenomenon, it can seem like an unending cycle.

I distinctly remember one day during a graduate seminar at Arizona State University, the professor made a comment that immediately grabbed my attention. He said that sometimes when our lives become too stable and potentially boring, or in a word too predictable, we are likely to introduce some sort of chaos into them. According to him, doing such a thing tends to make our lives a little more interesting. On the other hand, he mentioned that when our lives become too chaotic, we may then attempt to gain back some sense of stability and thus, some predictability.

There are no set time frames for when this tipping point will likely occur; it may happen slowly or it may happen quickly. But whenever something like this happens, we need to be aware that change is likely to occur; in whatever form it takes.

Remember in the previous chapter when we discussed The Reinforcement-Affect Theory which asserted that humans are attracted to the people who, “Say nice things; do nice things”? And remember I mentioned that there was a flaw in such thinking because the theory couldn’t explain why so many people become attracted to the individuals who, “Say bad things’ do bad things”? In that same discussion, I also promised that this book would look into both types of attraction. Well that time has arrived, so let’s jump right into it.

This type of attraction to “not-nice” behavior has presented philosophers, historians, psychologists and other authors who studied the subject of love with a challenge when conceptualizing attraction and its causes. For instance, Freud (1912) stated that:

“Some obstacle is necessary to swell the tide of libido to its height; and all periods of history whenever natural barriers in the way of satisfaction have not sufficed, mankind has erected conventional ones in order to enjoy love.” (Italics mine)

Other authors and researchers too, have also sensed this seemingly “backwards” effect. In her discussion of passionate love, Elaine Walster*, a more contemporary writer, puts it succinctly:

“… passionate love that flourishes in settings which would seem to thwart its development has always been puzzling to social scientists.” (Italics mine)

This seemingly “backwards” aspect of attraction makes sense however, when examined using the logic provided by Simmel. Since “not-nice” behavior is the cause of attraction in potentially half of all relationships, it needs more serious consideration.

Simmel’s logic challenges the one-dimensional logic of the Reinforcement-Affect Theory. Although it’s politically incorrect to discuss this type of seemingly unpleasant behavior, it must be acknowledged and incorporated into any model purporting to fully explain attraction. So keep reading.

Agree with it or not, to some people, mistreatment is often perceived as a reward. Some people like a challenge; the challenge to change someone from bad to good. Overcoming such a challenge would definitely require some effort. And we know that it takes some type of effort to cause a corresponding amount of attraction (love).

There are people who actually prefer the challenge of converting a “bad boy” into a “good boy.” Their thinking usually goes something like this, “Others may not be able to change them, but they will surely change for me.” And this type of thinking leads them to exert whatever effort they deem is required to get their love interest’s affection.

I don’t need to tell you that there are plenty of people who are attracted to jerks. Most of you can think of someone you know who is attracted to a jerk. It may have even been you at one time or another. In any case, these types that are attracted to those “harder to get” individuals tend to like to be challenged.

Below is Simmel’s direct quote from his book The Philosophy of Money.

“Because closing any such distance requires one to exert some sort of effort, the object’s ultimate desirability is measured by how much work (effort) must be put into closing that distance. In other words, the less work it takes to obtain an object; the less valuable that object is. But the more effort it takes to earn the object, the more value that object takes on.” (Italics mine)

After you finish reading through this book, you will probably ask yourself: Am I too easy to get? On the other hand, you may ask yourself: Am I too hard to get? Perhaps you may conclude that you are somewhere in-between.

One thing for certain is that when you understand how “value” is created, you will know what you need to do to become more “valuable” in the eyes of your partner (or potential partner). For example, if you are not being appreciated, you must make the person you’re with exert more effort to obtain your love and affection. On the other hand, if someone is pursuing you, and you want them to stop, you will also know what to do to become less “valuable.”

The following example is from a television series called JAG (1995-2005) which featured stories about Navy lawyers dealing with legal issues. In this example from the series, Marine LTC Sarah McKenzie (Mac) and Navy CMDR Harmon Rabb (Harm) have had “something” for each other since the inception of the series, but have never been quite able to work out any sort of relationship. In this particular episode, Mac informs Harm that she is going away on a temporary military assignment (TDY).

LTC Mac: “I’m coming back, you know.”

CMDR Harm: “I don’t want you to go, Mac.”

LTC Mac: “Why is it that you’re only like this when I have one foot out the door? Your interest always fades when I might actually be in a position to return it.”

CMDR Harm: “Mac!”

In a related matter, I distinctly remember my sister commenting about what one of her coworkers said when she asked him how come he never seemed to be able to get a girlfriend. He briefly thought about the question and calmly replied, “It doesn’t seem like I can bond with someone unless I first ‘sweat’ with them.” What he was saying was that he couldn’t bond with another person unless he survived stressful situations with any potential partner. In other words, he had to be with someone who made him earn their love.

This is also consistent with military bonding. Soldiers who endure the many difficult stresses of combat tend to bond with one another. And like combat, relationships often also involve a significant amount of stress. Thus, the same can be said of them. Some partners in romantic relationships may only be able to bond with one another if they first survive some sort of stress together.

Let’s take a look at how this works using a simple model I used to use in class. As a professor, I usually taught large classes comprised of hundreds of students. Therefore, in order to make class more personal and relevant to each of the students, they would “vote” on whether or not they agreed or disagreed with something being discussed issues by raising their hands.

One of the questions I would ask the class during the lecture on relationships was, “How many of you would pick up a penny you spotted laying on the ground?” When I posed this question to students, invariably, only a small number of them raised their hands.

Next, I asked the class about a completely different scenario by posing this question; “How many of you would pick up a $100-bill you spotted laying on the ground?” This time all of the hands go up. Seeing the stark change in the students’ “voting” patterns, I quickly ask them, “Why are there so many hands up now?”

All of the answers from those who chose to defend their position tended to center around the logic that the $100 bill is worth more than the penny. And they were all correct. Under normal circumstances, a person must work harder to earn the $100 as opposed to the minimal effort they would have to expend to earn the penny. Pennies just aren’t very valuable and are often tossed, left at a sales counter, or put in some sort of container and generally forgotten about.

So, ask yourself:

In your partner’s eyes, are you a penny?

Or are you a very much appreciated $100 BILL?

In other words, does your partner appreciate you, or do they take you for granted? If your partner takes you for granted, then perhaps you should consider scaling back your efforts to please them. I’m not suggesting that you be mean, or rude about it. I’m only saying that under normal circumstances, whenever we have to work for something, we appreciate and thus desire whatever it is that we have to work so hard to get (or to keep).

Keeping the information in the above few paragraphs in mind, think about how this dynamic would affect a relationship that wasn’t so smooth-going for the partners. If what my sister’s coworker said about dating, “It doesn’t seem like I can bond with someone unless I first ‘sweat’ with them” is true, then Simmel’s theory would explain why some people in a relationship can only bond with those partners (or potential partners) with whom they have had to suffer. These are the half of the population that becomes attracted to those who “Say bad things: do bad things.” Because of these social dynamics inherent with relationships, there are many of them that are fraught with drama and high levels of stress.

Before we move on to the next chapter, let me point out that we have not discussed how a person’s “looks” shape how these social dynamics are likely to play out. But I will say this much, the more attractive a person is, the more likely they will be attracted to the types who, “Say bad things, do bad things.” In Chapter seven, which explains the concept of Saturation / Deprivation, we will tackle this issue of attractive types’ tendency to become attracted to the “jerks” and to the “bitches.”

Take away points:

– We used Simmel’s model of what creates “value” to examine what makes people become attracted to the particular types of individuals that catch their eye.

– Simmel’s value theory avoids the mistake that the one-dimensional Reinforcement-Affect Theory made that assumes people only become attracted to those individuals who, “Say nice things; do nice things.”

– The more dynamic theory proposed by Simmel can explain why many people become attracted to people who, “Say bad things, do bad things.”

– This balanced and more dynamic theory serves as the core of the book’s reasoning about why people become attracted to the types they chose; and then whey they keep choosing them on a consistent basis.

– As you read through this chapter, I bet that you envisioned aspects of your own relationship (or someone you know well) in the descriptions of the related phenomena discussed.

– As you read through the rest of the book, you will think about how the concepts being discussed affect your relationships.

– Although politically-correct thinking says that relationships should mostly be full of love and affection, the reality is that many are instead full of drama and sometimes even violence.

*1971 Walster, Elaine. “Passionate Love.” In Bernard I. Murstein (editor) Theories of Attraction and Love. New York: Springer Publishing Company., Inc.